The Decked Canoe Archives

Assembled by Tim Gittins

Winning the Canoe Championship of America

from "Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Construction" by Uffa Fox, 1934

February 25, 1933, the Royal Canoe Club held its annual dinner and presentation of cups, and as winner of the two most important of these, it was my privilege and pleasure to fill them and pass them round the table.

In olden times, many a man met his end by being stabbed from behind whilst drinking, and often in old pictures a man is shown drinking with his back to the wall. This protected him from behind, and the old tankards had glass bottoms, so that those drinking could see any danger ahead. As the challenge and De Qulncey Cups were passed round, three men stood ll the while, the man drinking toasted the man on his left, while the man on his right, who drank last, remained standing, so the man drinking had a friend standing either side of him as was the old custom.

Through dinner we toasted canoeists the world over, and afterwards Roger and I departed, he to Oxford and I to the Isle of Wight, hoping that we should both take canoes to America in August, sister ships that would not only conform to the American rules, but also to the English.

Two days later, on the Monday, I sent the following cable to a friend, who is the oldest canoeist in America.

W. P. STEPHENS, 3716 Bay Street, Bayside, New York. Please send 1933 sailing canoe building rules, latest date for Challenge from England and date of Contest. Uffa.

Letters and cables passed between America and England, mostly cables from England, with the result that we challenged for eveything we could, Roger as the Royal Canoe Club, and I the Humber Yawl Club.

Then came the designing of our canoes, Roger helping with letters, full of ideas, from Trinity, and finally the canoes were designed to both sets of rules.

The American maximum beam rule forced us to design canoes 3 in. narrower than the English rule, whilst the English rule, demanding a 1/4 in. planking, forced our hulls 40 lb. over the minimum weight allowed in America.

Time alone would tell if we could afford to give away the 3 in. of beam under the English rule, where no sliding seat was allowed, and carry the extra 40 lb. of hull weight round the American courses, but we thought we might, and it was worth trying.

The rig would have to be different, as entirely different rules prevailed. Under the American rule, we were allowed 111 sq. ft. of sail, actual area, with a height of 16 ft., but no side stays on the mast, while under the English rule we were allowed 96 sq. ft., Y.R.A. measurement, with no restriction as to height or staying of mast.

The Americans had no limit to the depth of centre board, so, while racing there, we thought we would try a very deep one, which was impossible under the English rule, which only allowed a board to extend 1 metre below the canoe.

The American rules allowed a sliding seat, and the English did not, so by changing rigs and drop keels, and adding a sliding seat, our canoes were changed from the English to the American rules.

The American rule allowing a sliding seat, but no sidestays, made a fair amount of work calculating the leverage and power exerted by a man five foot out on a slide, plus the power of the canoe and balancing this against the strength and elasticity of hollow spruce spars. For, to win races, weight, and so strength, must be cut down to its limit, yet to carry away a spar is fatal.

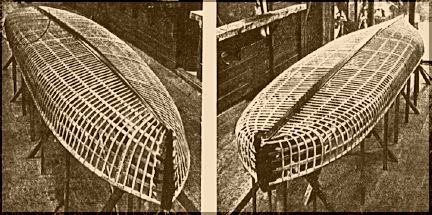

After the designing, came the building. Valiant and East Anglian were built upside down, for the bottom of any vessel is the part that decides her speed, and by building upside dovn this is always in view.

Moulds were made and set up on the stock, the keel, stem and stem post fitted, and the moulds ribbanded out. Next, the 3/8 in. by 1/4 in. timbers were steamed and bent 2 in. apart round the ribbands, and the first skin, of 1/8 in. thick diagonal planking, fitted. Oiled silk, stretched over the diagonals, formed the next skin, on which the 1/8 in. fore and aft plarking was fitted and fastened. After this the keel case, extending aimost the full length of the canoe, was fitted, followed by the deck beams and mast steps, and after six coats of varnish inside, the deck, of specially made 3-ply, was fitted, and fastened in one piece.

Spars were made and all was merry and bright, for we were ready for sea. The following verses by my wife will illustrate our pleasant thoughts during the building of Valiant and East Anglian.

Roger's New Canoe

There's a shaving in our workshop,

It's planed and varnished

too,

It trembles in a tiny breeze,

It's the keel of R.'s

canoe.

And gossamer hangs from the beams,

I ask, What

will that do

They tell me `tis the planking light

Of

Roger's new canoe.

There's wood so delicate at hand

No nails in this, but glue,

And `tis the deck, so I am told,

Of Roger's new canoe.

There is a tube both short and

spare,

Sans crosstree, stay or shroud.

It is the mast,

don't speak so loud,

Of Roger's fine canoe.

There is

a pocket handkerchief,

So small and dainty too,

It is the

sail of R.'s delight,

The sail of his canoe.

* * * *

* *

There's a flutter in our workshop,

There's happy

work to do,

Wish her good luck, a gentle touch,

She's

launched -the new canoe.

There's no mark upon the water,

No ripple, sure `tis true.

As Roger gaily glideth by,

In

his wondrous new canoe.

We had had some experience with the Enqlish rig, but none with the American, so this was the first to be tried out, and it proved better to windward than expected, and I easily beat an International Star Class Yacht to windward in both light and strong winds, so, as far as windward work went, we were contented with our canoes, for winning, after allowing the Star Class 15 minutes in an hour, showed this to be a good rig.

Then the English rig was fitted in tabernacle, which allowed the mast to be reefed in strong winds. This too seemed good.

The Royal Canoe Club's Annual Meet came all too soon, and almost every new yacht or sailing boat finds her first class race too early for her liking. Roger took Valiant over to Southsea on board the passenger steamer, where his brother met him with a trailer and motored them both to Langston

The following Wednesday, I sailed East Anglian across, well reefed, with no jib, as it was blowing hard from the south-west.

At the end of the two weeks' meet, I had lost the De Quincey Cup to Eric Freeman in Genetta, and the Challenge Cup to Roger De Quincey in Valiant, and on July 22 we sailed Valiant and East Anglian to Cowes in company with Aquamarine, having just a week in which to fit out for America, as we were sailing aboard the Empress of Britain on July 29.

That week was spent making spars and masts, varnishing our canoes and doing the hundred and one jobs we thought necessary. On Friday 28, we shipped our canoes and gear, including ten spare masts, to Southampton and aboard the Empress of Britain, and returned to Cowes for the night. This gave us a double start, which is useful.

In this case, it enabled us to leave again, heavily laden with gadgets we had thought of since the previous day.

Roger and I left England full of hope, for we hoped that we should win the American National Championship and also their International Trophy, and return with, as well as these trophies, a rule from America that would be acceptable to England, and so unite canoeists of both countries. If we succeeded in obtaining this, a canoeist would henceforth be able to race in both countries without the handicap of having to design and build to two entirely different sets of rules.

The Empress of Britain was most kind to us, and we spent many happy hours in the carpenter's shop, making spare tillers and paddles.

Later, wbilst I made a storm jib, Roger made the brake for his centreboard winch; this brake is Highfield's patent, and due to the smallness of the winch we were unable to buy a brake for it, so, as the oniy way a man can pass to windward of the patent law is to make the article for himself, Roger was forced to make his brake.

Our voyage across was spent very pleasantly, making gear for our canoes during the day, and dancing at night. Going through the Straits of Belle Isle we saw an iceberg, shaped like an old Spanish galleon with a high stem. This did not seem at all out of place, far although it was summer it was very cold, owing to the Labrador Current, which, bringing this iceberg south, gave us food for thought.

Here we were, in the same latitude as the south of England, where it was very hot, meeting icebergs, and not being surprised, this vast difference being due to the ocean currents, for the warmer water of the Gulf Stream. setting across to the British Isles, makes it possible for tropical trees to grow in the south-west of England, whilst the Arctic Current, coming down the Labrador Coast, is the cause of the coldness of that land.

Looking at the high bold land close aboard that morning was painful to our eyes, that for almost a week had been used to looking out into space with an unbroken skyline. Now, looking on this high land so near to us, our eyes found difficulty in focussing it, and yet for almost a week we had been able to go down, after being on deck, and feel no pain in our heads, when we looked at the good food on our table, which was far closer than the land we now saw.

We arrived at Quebec on August 3, five days out from England, which is very fast time indeed. We left Quebec at 6.00 p.m., and as there was no room for our canoes on this train, they were to leave by the next at midnight.

This gave us six hours in Montreal, in which to find a hotel, turn in, sleep, turn out and meet the canoes. So after a nap at the "Windsor", we met the canoes at 7:00 a.m. and switched them over to the National from the Pacific Railway, arriving at Gananoque junction at noon. We then took a tiny train to the town waterfront, and had our canoes ready for sea by tea time.

Our destination, Sugar Island, was in sight, three miles away, and we were looking forward to our sail there. Just as we were about to put to sea (in the river St. Lawrence) Jack Wright, the Commodore of the American Canoe Association, came along in his launch. He was a friend in need, for we had loaded our canoes right down with suitcases, spare masts and gear, all of which he kindly took aboard his launch, and the three of us made for our tents on Sugar Island, the Commodore steaming in his launch and Roger and I sailing our canoes.

Doing 6 knots, we were soon abreast of the island, with its tents, hills, trees, rocks and sandy bays, and hauling our wind reached past Headquarters Bay, and luffing into New York Bay, were welcomed by Dudley Murphy's wild scream of "Whoopahee", a most unearthly yell, that he had learned from some Indian canoe men who used it as a greeting to other Redskins they met.

Rolf Armstrong had met us in Mannikin, and his canoe, with our two, the commodore's launch, and the other canoes all ready there filled the bay completely. We pitched our tent with the help of about ten others, then put up our beds, and piled all our gear into the tent, suit cases, bags of sails, ropes and gear, till it looked just as untidy as our cabin aboard the Empress of Britain had done, so we felt at home right away. The poor tent did not even have a chance to look tidy.

The commodore invited us to dinner at his tent across the bay, after which we went for a sail in the light of a full moon.

The island looked very fine by moonlight, while in front of headquarters' tent there was a huge red glow from the camp fire, with figures passing to and fro in front of it, and the sound of their voices as they sang came floating across the water to us. An island has more charm than any other part of this earth, and this island tonight in the mooniight seemed very lovable, and we were both happy and content as we sailed about its bays. It was to be our home for two weeks, we were to know its trails, live with its people, share meals with them in their tents, sit round the camp fire at night with them singing and yarning, and learn to love them all, for their kindness and open-heartedness. They named Roger and I the Babes in the Woods, and it was very nice to be babes to such people.

The next day (Saturday) Roger and I dressed in our best, white tops, white flannels, neckties and white shoes, for the flags were to be hoisted, and the camp officially opened. After the speeches, and many kind words, we set sail for Gananoque: Rolf Armstrong in Mannikin, with Roger all alone in Valiant, and Mrs. Rolf with myself in East Anglian. There we ate ices, bought several small tools we needed, and sailed back to Sugar Island, Mrs. Ro1f coming back with Roger, while I sailed home alone.

Sunday was the day of rest, with tea at Squaw Point, where we saw what comfort there could be in a tent. Mrs. Coggins must have been surprised to see Roger and I drink seven cups of tea each, but we thought we should not often have a chance at tea in America.

That night we went to our first camp fire, and the commodore asked me to sing, so I sang "The Bosun's Story", of how he discovered the north pole by harpooning a whale and being towed there by it, and then being knocked back again by the whale's tail. On Monday we all arrived at headquarters' tent with our sails for measurement, and we found that ours were 11 ft. under their allowed area. They were correct on the foot and luff, but the roach had gone out of the leach, due to the fact that a sail is like a piece of elastic, which, when stretched, becomes narrower, although longer, and therefore measures the same area as when made, but in a different way.

Tuesday was our first race in American waters. This was a tuning up race, with a nice breeze, and we averaged 4 1/2 knots round the course. I hit the first buoy, by catching my drop keel on its wire, and so pulling it towards me.

Committees should moor turning marks with chains, but if with rope, they should have a weight 10 ft. or so below the surface to take them down plumb, so that they cannot be caught by the keel of a boat rounding them. In this case, I asked what I should do and was told to carry on, as it was a tuning up race, and we all wanted to see how our canoes sailed, but I should not put any canoe about or take her wind, so keeping clear, I completed the course, and finishing second, reported to the committee, and was disqualified automatically. Ro1f Armstrong was first with Gordon Douglas third and Roger fourth. At this speed our canoes and the Americans were equally matched, below it the latter would be faster and above it we should win.

Flags on mark buoys are not very good as guides, for if dead to windward, or dead to leeward, they are invisible, blowing either directly away, or directly toward, the man trying to see them. Besides this, in uncertain winds they flip out, and often just catch a boat rounding close, and so disqualify her. Here, the American Canoe Association had solved the flag problem in a cheap and masterly way. They had tacked shiny tins or buckets upside down on the buoy poles, and they glistened and reflected the sun's rays like mirrors. On dull days, catching what light there was, they showed up brightly as well, and bing round showed equally well from all angles.

The camp fire that night was to see the crowning of the king of the island with speeches by him, the Prince of Wales, and Knights of the Bath and Garter. Then these were to be impeached, and a dictator appointed for the duration of the meet. I was chosen King, and crowned, which was all very well until my son, the Prince of Wales (George Denhard, the chairman of the New York Canoe Club) spoke, and he rather let me in for things. However it was not long before the dictator was put in power, and then the fun began. The commodore was made privy councillor, and there was a bees' nest in one of the privies. Mayors were made, cabinets formed and everyone was given a job. After this we had a sing-song, and then to our tents and sleep.

Wednesday was the first race for the Admiralty Trophy. The rules for this race stated that one leg of the triangle was to be sailed, and the next paddled, so by doing this we sailed and paddled over each leg of the triangle in two rounds. It was a paddling start, and a race we had not bargained for, so we knew little about it, and as I had never before paddled a canoe, things looked black. They looked even blacker when my sliding seat fell overboard at the start, and I had to go back and recover it. However, at the end of the second leg, which was a sailing leg, East Anglian led the fleet. Then came another paddling leg, and here again I became unbuttoned, for I had stowed my sails, pulled up the drop keel and stowed the sliding seat, and was leading the fleet nicely, with enough lead in hand to hold back the faster paddling canoes of the Americans, when my jib broke adrift, and although it was stopping me as it blew aft, I thought it far better to stow it again, so walked up on the fore deck, and stowed it neatly. Then, coming aft, I forgot the drop keel was up and East Hnghan capsized. I tried to right her by standing on the tiny piece of drop keel, that was showing, but could not do it, so swam round and pushed the drop keel out. Even then I could not right her, so rigged the sliding seat, and with this and the drop keel, she was easily righted, and I was all ready to paddle on, when the paddle was seen floating twenty yards away. This meant another swim for the paddle, but at last we were away again. When the next sailing leg came, my sails were like a prune, being a mass of wrinkles, but halfway through this leg, which fortunately was a beat, the wrinkles all came out, and East Anglian was first round the weather mark, but not far enough to hold one of the faster paddling American canoes on the next leg. She passed me halfway down this leg, and East Anglian could not catch her again on the last reach home, so finished second.

The wetting of the sails, their wrinkling, and then coming as good as gold again after they were dried, showed me the value of using rope for luff and foot, instead of wire, for the rope shrinks and swells with the canvas, whereas the wire remains constant, and so, after a sail has been wet on a wire and shrunk, it is probably stretched unfairly.

That night Roger attended the fancy dress ball in a child's rompers, whdst I was rigged out in a grass skirt from the South Sea Islands, two very nice cool costumes.

On Thursday the Mermaid Trophy was raced for. This trophy was given by Leo Friede for 16 ft. by 30 in. canoes, as he was a great lover of these little canoes, and for years had won the National Championship in one of them, and twice successfully defended the International Trophy in Mermaid, his 16 ft. by 30 in. canoe.

Our canoes were 17 ft. by 39 in., so Roger borrowed a 16 ft. by 30 in. and I was loaned the Damosel, another 16 ft. by 30 in., and we felt very unsafe in these narrow canoes, which, with no one in to balance them, capsized by themselves. However, we managed to sail round the course without capsizing, in spite of the fact that our athwartship tiller fouled the sliding seat. Ralph Britton won in Jonah, Gordon Douglas was second in Nymph, Tyson third in Oske Wow Wow, and I was fourth and Roger fifth.

In the afternoon, the second race for the Admiralty Trophy was held. The wind was very light, and away we went sailing slowly round three rounds of the triangle. For what seemed hours I lay 100 yards off the finishing line becalmed, with the rest of the fleet farther astem, when the time limit expired, and the race was called off.

This night the camp fire was under the care of Dr. Wakefleld, a past commodore, and he built up the biggest fire of the whole meet. The piano was brought out, and many fine songs were sung. The charm of a camp fire lies in the warmth of its light; it is soothing and one looks into it, and dreams pleasant dreams, whilst, when a song is sung, the listeners can float away in their little dream-boats with the singer, for a fire, and the twilight of the fire, stirs a man's imagination.

The sunrise and sunset aare the two most beautiful parts of the day, and their charm is the charm of the fire. Then, too, outdoor people watch the sun rise and set, for then the Lord tells those that understand the weather for the day or night.

Friday, we sailed the postponed race for the Admiralty Trophy. This time the breeze allowed us to finish within the time, and East Anglian won, with Roger second, Chip Tyson third, and Gordon Douglas fourth.Saturday came with a smart S.W. wind, and the paddling race for the Admiralty Trophy was held. As this was paddling only, Roger and I were advised to take this very easily, as we could not hope to beat the faster American paddling canoes, and the first heat for the National Sailing Trophy was to follow immediately afterwards. But we both agreed, that if we were going to race, we might as well win or burst! So we took out the drop keel, spars, and as much gear as we could, and came to the starting line to win.

The course was straight along the island to Stave Island, wind on the weather quarter, strong, so as soon as I could I headed East Anglian out to sea, where, although it was rougher, the wind was stronger and more of a help, as I stood up to paddle with a fair wind. Away we went, white water flying off our double paddles, and the result was that East Anglian finished second unexpectedly, only 30 yards astern of the champion paddler of Canada, and so won the Admiralty combined paddling and sailing trophy by 1 point.

We were towed back to Headquarters Bay, and there quickly rigged our canoes with drop keels, masts, sails and sheets, and were soon ready for the first heat of the sailing trophy. The wind was too strong for most of the American canoes, so East Anglian won, with Valiant second, Gordon Douglas third in Nymph, Rolf Armstrong fourth with Mannikin, and Mab, who had left her mainsail ashore and set two mizens, fifth. So only five finished out of nine starters.

After the race Roger went to Gananoque to see the paddling races there, while I stayed at Sugar Island to try out our storm jibs, and see if they were good, in case the wind came stronger. They seemed good, so after sailing three times round the island, I set off for Gananoque to watch the last of the paddling races. By this time the wind was easing, and only about half the paddling canoes were swamped in this race. The war canoes, with fifteen men in each, made the finest sight, as they tore through the water. We had tea aboard Frank Palmer's yacht, and returned to Sugar Island for dinner. The island looked very fascinating as East Anglian approached it in the twilight; the hard wind had eased with sundown, and there was time to think of the peace and restfulness of living in tents, on an island with no roads, no motors, nothing except rocks, trees, bushes and wild animals. And it was pleasant to think of, and look upon this island, in the evening light. That evening, after dinner, the executive meeting was held at Headquarters Tent, and the American Canoe Association made Roger and I honorary members for life. This was a great honour, and one we felt deeply. And so to bed, feeling happy and contented.

Sunday was another day of peace. In the morning Roger and I went for a sail off the weather side of the island, as there was a smart breeze. I had my storm jib, and he, with full sail, was faster, as was to be expected, for there was not enough wind to shorten sail on our canoes with sliding seats.

Then, after lunch, we were all peacefally yarning in George Lewis's tent, when in burst Ted Coggins, who had just arrived at camp, wanting to be convinced that our canoes were faster than the Americans in hard weather. He bet the red pants he wore that he could beat Roger and I.

Now two to one is unfair, and as I was dressed for church, Roger took the bet, and the pair went to race, whilst we went on to church in Headquarters Tent.

Rolf Armstrong went out as race officer aboard the committee boat, and started them, while we sang hymns ashore. Suddenly, whilst the lesson was being read, Doc. Wakefield nudged me, and looking out to sea, I saw Ted capsized, and Roger roaring along in fine style. Then Ralph Britton's voice suddenly tailed off faint in the next hymn, and looking up, I saw him twisting his neck round to watch the race, for as he was in the choir he had his back to the sea. So our service and race went on. Roger won the red trousers, and convinced Ted that our canoes were faster in wind, a fact which had been proved beyond all shadow of doubt the day before.

That evening Ralph Britton took us to his island home the other side of Gananoque to dinner, and then in the twilight, Ralph, Roger and I explored the group. The magic and fascination of these small islands was strong that night, and it was hard to leave them, and return to our own island and bed.

Amongst the Admiralty group we saw the Natural Open Air Cathedral, surely the finest place in which to worship. People did go there every Sunday evening, sitting in their canoes and boats, whilst the parson conducted the service from the natural pulpit ashore

The parson who preached at our service at Sugar Island in the afternoon was a brother-in-law of Ralph Britton, and he told us the story of a brother clergyman who was appointed to congress - and when asked if he prayed for congress, he replied that he looked at the congress and then prayed for the nation.

On Monday came the second heat of the National Trophy over a windward and leeward course with a nice breeze from NW, which shifted during the race, and so spoilt the beat for the last two rounds. At the end of the first round, East Anglian led, and held her lead till the fifth round, which was won by Mannikin. Then, as the wind had shifted still more to the south, the last beat became a close reach, but Mannikin not noticing this, lost her lead by holding on to the starboard tack, when by coming about at the buoy she could have laid the course on the port tack. So East Anglian won this race with Mannikin second, Valiant third and Douglas fourth.

This night was the commodore's ball, and Roger and I wore our dinner jackets in his honour. but they were so hot and uncomfortable that we changed them after about two dances.

Tuesday was the third and final heat for the National Championship in a light wind, when our canoes and the Americans were the same speed. East Anglian had only to finish fifth in this heat in order to win the American National Sailing Championship, so I sailed a very careful race, feeling rather like a married man playing cards who will only go nap when he has the ace, king, queen, jack and ten of one suit, and in spite of carefally sailing well clear of every canoe and buoy, East Anglian only lost first place by 5 seconds to Gordon Douglas in Nymph, with Mab third, Roger fourth and Oske Wow Wow fifth.

And so East Anglian had won two American championships for the Humber Yawl Club of England, the combined paddling and sailing, and the decked sailing, and I felt at peace with all the world.

There was just one other championship, for paddling only, and the fact that the American canoeists one and all asked me to train for this, and try to win it in 1934, illustrates their sportsmanship and love of sport.

On Wednesday, the Paul Butler Trophy was sailed for. It was Paul Butier who adapted to the canoes the Indian trick of sitting out to windward on a plank. These Indians gauged the force of wind by men, a two-man breeze was one where two men sat out at the end of planks, and so on. Paul Butler was a tiny man, and so light that he did not stand any chance in strong winds, so he put the sliding seat on his canoe in the [eighteen] eighties, and won races, until the others fitted them also, and now most canoeists use a sliding seat, although on this side of the Atlantic we have a rule against them.

The sliding seat is of great advantage to canoe sailing, for the power of a sailing canoe is that of the weight of its crew sitting to windward. In England, we are forced to lay out, which is a strain, but, with the sliding seat there is no strain, as the crew simply sit out at the end of the slide. Besides being easier and more comfortable, this is also drier, for the seas, breaking over the canoe as she is driven to windward, do not touch the man on the sliding seat.

Paul Butier's widow gave this trophy, and it is a very pretty cup, rather like a Gaelic quaich with a handle on each side, a Scotsman being so afraid of losing his drink that his cup was made so that he could hold it with both hands.

Roger won this race, and I finished 12 seconds astern of him, with Ralph Britton third, in Jonah. In the first beat to windward I made a mistake over one tack; Gordon Douglas in Nymph was second and he stood on for about 5o yards, and then came about to port. As he knew the waters and was, moreover, second boat, I put about too; then we came round again, as I had his wind, and away we stood for the islands to windward. By this time, however, Roger, who was a very close third on rounding the buoy, had pulled out ahead, as he had not tacked twice in quick succession as we had, and we were unable to catch Valiant during the rest of the race.

Thursday was the last race for us of the meet, and as winner of the National Trophy, East Anglian was not allowed to race for the Mab Trophy, so I went aboard the committee boat, as one of the officers of the day.

It was a fine race to watch, as it was another day when the wind was light enough for the English and American canoes to be of equal speed.

The first three canoes kept changing places during the beat to windward, first one ahead and then the other as the puffs shifted or the others made false tacks. But in the end Rolf Armstrong won by a minute from Roger, with Ralph Britton third, and Adam Whal fourth.

Then came lunch, and whilst Roger went to Gananoque to do some shopping, I rigged our two canoes, and packed things at the tent, for that afternoon we were to sail our canoes to Clayton, and so enter America for the first time. It was a fine sail there with a strong wind, and on the beat Valiant forged ahead of East Anglian. Murphy and Ralph Britton escorted us over, and went bondsmen for our canoes, otherwise we should have had to put down money amounting to the third of their value against their being sold to the Americans.

We sailed them into a yacht yard, and stored them in a shed, then went back to Sugar Island for our last night's sleep, after we had been presented with our cups and medals, and the former had been duly filled and passed round. This was a joyful and yet sad evening, for it was our last, and we made the most of it, Roger leaving for Gananoque at 2.00 a.m. to visit his uncle in Vermont.

Heavy rain and wind squalls.

On Friday morning it rained hard, and was not at all pleasant for packing things from our tent, but at last it was all over, and Douglas took Rolf Armstrong, his wife and canoe as well as myself to Gananoque for the ferry to Clayton. At Gananoque I had to change the customs papers of our canoes for others to let them into America. Then we boarded the steam ferry for Clayton, and as she steamed past Sugar Island the friends we had left fired the cannon and dipped the flags, a very sad morning, but all things come to an end, and that camp did, although its memory will live always.

Arriving at Clayton, I paid five dollars for a poor old trailer, last used as a barrow for dung, and into this we fitted a new oak shaft, with steel plates and bolts, to fit the back of Rolf`s Packard. He tore off to Watertown for the trailer's licence, after we had weighed it at a baker's. Then he loaded his canoe Mannikin on the top of the car, while I loaded East Anglian and Valiant on the trailer with their ten masts, drop keels, sails, etc. They brought the springs down flat. We stopped for dinner for an hour, and then on with the work till midnight then to bed.

Saturday morning we were up at 4:30 a.m., for it would be a long drive to New York and an early start is half the battle. So the car with Mannikin on top and four of us inside started off for the trailer at the shipyard, and there bolted it to the buffers at the stern of the car. We were very anxious about the five-dollar trailer, as it had a heavy load aboard, which was still valuable, as the International Canoe Trophy had yet to be won.

After 15 miles our fears were justified, for the stem of one of the tires sheered off, which made the trailer wheel wobble, and almost shook the canoes off. We stopped, unshipped the trailer, and Arthur George and I took off the wheel, whilst Rolf and his wife drove into Watertown for tools, with which to fit another tire, Mannikin lookIng very cheeky on top of the car all the way.

After the repairs off we went again and arrived at Watertown without further trouble. But the strain began to tell on our nerves, and we were so pleased to be able to relax for a few minutes that breakfast was very noisy, and so full of laughs that people thought we were tight.

I had been riding on the trailer some time to watch and listen to things there, and the noise of a man chopping wood caused my heart to stop for a moment until I realised what it was. After breakfast we left with a quantity of wire and two horseshoes for luck.

About 5 miles ftom Watertown the bolts holding the buffers to the port quarter of the car carried away, and we had to wire these on. At the same time we wired the starboard side to make sure of these though they had not yet gone, so we continued adding new wires before the others gave way, and consequently they never failed.

And so we came to the Mohawk valley, through which our course lay. This valley was once the home of the Mohawk tribe, and to see its beauty spoilt by roads and railways made me wonder if civilisation is a blessing or a curse. That afternoon I was sure it was a failure, for the redskins, once a vigorous, fierce, and although cruel, an admirable race, were no more. And it seemed wrong, for they were the natives of North America. White men are so sure that their gospel is the only one, and they teach it to strong vigorous races, who drop their own strict moral laws for it, then, following the gospel teachers, come others with fire water, and soon the race fades and dies like a poisoned tree.

With all our boast and pride of civilization, people still starve in thousands in a land of plenty, millions wither and choke in big cities, living lives humans were never meant to endure, and all because of the introduction of money into the world, the thing that should have made living simple, destroying the simple life.

On and on we went, till late at night we reached New York, and then passed through its steets at 3:00 a.m., seeing crowds of people turning the night into day. We crossed to Long Island by the steam ferry, finally arriving at Rolf's home at 3:30 a.m. after 23 hours of driving all in New York State, and it was not until then that I realised that each state was as large as a country of Europe. Then I gained some idea of the size of North America.

At the end of our journey we were met by dear old W. P. to whom I had sent the first cable some months ago, that started this adventure, and with whom I was to stay for a week or so. We had arrived a the scene of the International Canoe Contest (Bayside) without a scratch on any of the three canoes, weary but triumphant.

On Sunday W.P. and I sailed over to City Island in Snicker Snee, a Humber canoe yawl. for W.P. is a member of the Humber Yawl Club. In the afternoon we unloaded the canoes from the trailer, and then visited the New York Canoe Club House. or rather all their furniture on a barge, for the clubhouse had been sold

On Monday we again measured our canoe sails with the same result, that we were 11 sq. ft. under area. So we prepared plans for a larger suit with more round to the leach, which would, when stretched, come out to the designed roach. We decided to give a 6 in. round in the luff of the mainsail, a 21 in. round to the leach,a 4 in. round on the foot, 4 in. round to the luff of the jib, and 1 1/2 in. round to the foot and leach of the jib. This would disappear soon after the sail was used.

Sunday, the new sails were measured, and the mainsail was over area, so we chopped 9 in. off the foot at the clew, lifting the boom that much, and reducing the round of the leach to 1 ft. 6 in. The jib was just right.

All the week we were preparing the canoes for their last effort in America, rubbing down and varnishing, taking off our keel bands, varnishing spars, fitting battens to our mainsails, and all the many little things one can always do to a boat before any race. The Americans, too, were doing the same sort of things.

On Friday the first race of the series was held, to select the two American defenders. There was a smart breeze, which capsized many, carried away the masts of others, and generally shook the fleet up, while East Anglian sailed over to City Island without any trouble at all, to see Ratsey about our new sails. On the way back, an 8-metre tried to catch her, but could make no impression at all, for we were on a reach. The next morning with two aboard, East Anglian, with Valiant's new Ratsey sails, crossed the line a minute or so after the American trial races had started. We easily made the weather mark, while the Americans had to tack for it so our new sails promised to be good, for besides holding a higher wind, we were footing faster. Down wind we were only as fast as the rest of the fleet, and reaching they were faster. Then we drifted all the afternoon, whilst the competitors, in the third race, were lying becalmed. This race was finally called off and the American team selected was Leo Friede, who had twice before defended the New York Canoe Cup successfully, and Walter Busch, a young athlete.

Monday, the mainsail was taken to Ratsey's to be cut, and a new suit ordered for East Anglian, the same size. And we still found work to do on our canoes.

We all went into New York to dinner on Tuesday with Leo Friede, the committee and all the canoe racers. The view from the top of his roof was very fine, for the buildings of New York are impressive, like giant's fingers flung up against the sky.

On Wednesday the sails of our two canoes were ready, and they were measured with the American's sails in Ratsey's sail loft at City Island and found just under area, so we were settled and away we sailed for Bayside across the sound. This was a beat to windward against a light breeze, and as we were trying our new sails, was just right.

Earlier in the day we had sailed over from Bayside, Rolf in Mannikin, his wife in the Currey Racer, which we easily beat to windward, laying a point higher and going as fast, and Roger in Valiant, with myself in East Anglian. We had a very short sail in our canoes on Thursday, and devoted the afternoon to fitting battens in the mainsail; whilst the canoes were on shore. We also set the sails in the light wind to see how they stood. We had pockets right across the sail for long battens, but with a batten right across a sail it is possible to be sailing with the mainsail starved of wind, and not know it, till suddenly the bartens allow it to flop across, and then one realises that for some time the mainsail has been starved of wind. We finally ended with the second from the top batten right across the sail, but the rest of normal length, making one long batten and six others.

Friday dawned with a light air, just what we did not wish to see, and out we went to the triangle to start. We were surprised at being sent round the course, so that we had no beat to windward. There was a dead run on one leg and this meant that the other two legs were reaches. We should have been sent round the other way, when the run would have been a beat.

At the start, Roger looked after Leo, while I looked after Loon, but as they were faster in the light going they slipped out from under our lee by the time we had reached the first buoy. The end of the first lap saw Friede well ahead, Busch second, and Roger and myself almost 2 minutes astern. These times were unaltered for the rest of the race, for the wind lightened slightly, the only difference being that in the third round Busch took the lead from Friede and I went ahead of Roger. Then, on the last leg, I caught the mooring rope of the mark buoy on my drop keel, and this pulled the buoy on to East Anglian so she retired, leaving Roger to finish alone for England.

During the trial races Roger and I had sailed close to the buoys, and found that they were moored with chains. and could be cut very closely, so all was well, but then these trial races had taken place in the shallower waters in the bay, and when the course was laid out for the international contest in the deeper water of the sound, these chairs were not long enough, so ropes were used.

After the race we all gathered aboard the committee boat and yarned. The speeds that day worked out at 4 1/2 knots, as 2 hours had been taken to do 9 miles, and as there was no windward work, we had stood no chance at all.

But we hoped for more wind on the morrow.

| FIRST LAP | ||

|---|---|---|

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 27 min 34 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 29 min 0 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 29 min 17 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 29 min 24 s |

| SECOND LAP | ||

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 57 min 35 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 57 min 46 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 58 min 58 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 59 min 19 s |

| THIRD LAP | ||

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 27 min 15 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 1 hr 28 min 41 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 1 hr 30 min 15 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 1 hr 30 min 28 s |

| FINISHED ELAPSED TIMES | ||

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 59 min 22 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 1 hr 59 min 48 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 2 hr 1 min 17 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | (Hit buoy and retired |

That night, after we were in our room, Roger and I had yarn over things. To win the cup, we had to win the next two races, and if we could only win the next, we should probably win the last whatever happened, for we should be on the upward, while the others would be on the downward path. So we thought, if one went ahead and won while the other stayed back and played about with the American team, and held them back, all would be well.

As I was the elder it would be better for me to play Mr. Nuisance if possible, for my football position had been centre half, where I used to fairly successfully prevent the other team from playing football, so I hoped to be able to hold back the two American canoes. By the rules, only the first canoe home counted, so it would not matter where

I finished, as long as I attracted the American canoes from Roger, so that he could finish first.

Saturday morning came in with a flat calm there was not a ripple, and the race was timed for 11:00 a.m., at which time there was still not a breath of wind, so the committee said they would postpone the race, and give us half an hour's notice before the start. So we put our canoes tidy, and did odd jobs to them. Then the four of us, the two Americans and we two English, went off to lunch together. We were still feeding happily when the committee routed us out to race, and Roger and I were delighted to see a smart breeze.

The wind this day was in exactly the opposite direction from the day before, and as we were being sent round the triangle the same way, it meant that we should get a good beat to windward. Everything looked good to us, but to make sure we thought I should still be Mr. Nuisance. Away we went with two reaches, and then a beat to windward, and at the end of the first round Valiant was first, East Anglian second, with Mermaid third and Loon fourth.

Now, my job was to delay the first American canoe till the other one came up, and then try to hold the two back or at any rate keep them from causing Roger any fear. So on the second reach Mermaid and East Anglian luffed, bore away and fought like two wild cats, all of which time Valiant pulled out ahead and Loon caught up. As we approached the leeward buoy East Anglian was in front with Mermaid and Loon close astern. This would never do, for it would mean that I should round first, then Mermaid would split tacks to clear her wind, and I should be forced to tack on her, which would let Loon away on the other tack. So East Anglian slowed up, and Mermaid went round the buoy a length ahead, then round came East Anglian shooting up on Mermaid's weather quarter, so preventing her from tacking. Later, Loon came round far enough astern to have a clear wind. So she stood on the starboard tack as we were, and did not tack until Mermaid had been driven well under Valiant's lee, where she could bring nothing but delight to Roger's eyes when he saw her. I went off to make sure Loon did not pick up any advantageous shift of wind, so the game went on. The newspapers reported that Mermaid and East Anglian changed places five times on one reach, and this illustrates the combat.

| FIRST LAP | ||

|---|---|---|

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 23 min 6 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 23 min 40 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 23 min 40 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 24 min 20 s |

| SECOND LAP | ||

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 46 min 8 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 47 min 27 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 47 min 40 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 49 min 3 s |

| THIRD LAP | ||

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 1 hr 9 min 9 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 1 hr 10 min 8 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 10 min 22 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 1 hr 12 min 22 s |

| FINISHED ELAPSED TIMES | ||

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 1 hr 32 min 0 s |

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 1 hr 33 min 24 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 1 hr 34 min 11 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 35 min 13 s |

A nine mile course in 1 1/2 hours equals an average of 6 knots, so we were travelling well over 6 knots all the while, as there was a good turn to windward, whereas on the previous day there had been no windward work, so we had only done 4 1/2 knots through the water. As before, we all met aboard the committee boat and yarned. That night Roger and I decided that it was worth while one of us being Mr. Nuisance, and that it was really best for me to play this part, if practicable, but if not, Roger should do it.

The morning of the final race was just what the doctor had ordered for us, as a strong wind was blowing from exactly the same quarter as the day before, and we imagined we should be sent round the triangle the same way, but as we approached the committee boat, running dead before the wind, we were surprised to see the signals hoisted for the course the opposite way round. So we started with a dead run to the lee mark, with no chance of a windward leg, unless the wind shifted. East Anglian led over the line and then started her attempt to hinder Loon and Mermaid hoping to get Valiant away, but as Valiant rounded the lee mark, her foresail gybed round and fouled her foremast, and so she was practically hove-to. East Anglian then fought Loon and Mermaid, and soon first won first place, leaving Roger astem. However, he soon had Valiant sailing again, catching Mermaid and then Loon, but instead of coming on ahead into first place, while I dropped back to the enemy, he stayed with them, and attacking Loon, refused to come on. Roger in Valiant was doing such a good job with the foe, that I in East Anglian sailed, reaching and running round the course quite happily, until there came a heavy shower of rain at the end of the second round, which knocked the wind down to almost a calm. Then the pace slowed, and Roger had to fight very hard to keep the now faster Loon back, but he held her until the wind freshened again at the end of the third lap and all was well once more. On the last lap, after rounding the leeward mark, the wind shifted a little, making the close reach to the weather mark possible with sheets slightiy eased. So East Anglian romped down this reach, and Loon, rounding the leemark behind Valiant, tacked at once to starboard. Roger, although he could easily lay the weather mark, swung about with Loon and it was not until a motor yacht, under way, put Loon about, that Roger came round with him. Then they both reached with sheets well off for the weather mark, round which East Anglian had already passed to reach across the line and win, thanks to her team mate's aggressiveness.

| FIRST LAP | ||

|---|---|---|

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 23 min 0 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 23 min 54 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 24 min 7 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 25 min 47 s |

| Leo Friede's mizzen sheet broken | ||

| SECOND LAP | ||

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 54 min 14 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 54 min 27 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 54 min 32 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | 54 min 50 s |

| Americans closing up in light wind - Roger fighting hard to hold them. | ||

| THIRD LAP | ||

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 1 hr 10 min 16 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 1 hr 11 min 14 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 11 min 36 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | Gave up - mizzen sheet parted again. |

| FINISHED ELAPSED TIMES | ||

| Uffa Fox | East Anglian | 1 hr 27 min 52 s |

| Roger De Quincey | Valiant | 1 hr 30 min 1 s |

| Walter Busch | Loom | 1 hr 30 min 18 s |

| Leo Friede | Mermaid | DNF |

So the International Canoe Trophy came to England for a year, with the other canoe cups we had won from the Americans.

These were the fastest times of the three races, but as there was no windward work, the speed through the water was far below that of the previous day, 9 miles in 1 1/2 hours equals 6 knots

So after 48 years, the canoe trophy left America, the first time it had ever been won from them during all those years

Roger and I were very pleased and proud at having beaten the best canoe sailors of America on their own waters, but this joy was tempered with a strange sadness hard to define. They had welcomed and opened their hearts to us, taken us into their tents and homes, and we had been the best of friends before and throughout the races, and now that the races were over, were better friends if possible than before.

Only in adversity and defeat does real sportsmanship show up, as it is easy to smile after victory, yet when East Anglian swept across the line to win the deciding race for the International Trophy, such a shout of joy and noise of tooting went up from the yachts witnessing the race, that I felt a lump rise in my throat. For here were Roger and I, strangers in a strange land receiving cheers that could not have been louder had they been given for Leo Friede and Walter Busch.

And so our canoe races in America ended enjoyably. They had been marked by clean sailing with no protest, or the need for one, throughout, and this added greatly to the pleasure the races had given us.

A few days later the International Canoe Trophy was presented at the New York Athletic Club, by William P. Stephens, and a challenge read out immediately afterwards. Roger and I said we should like to give them a trophy for their canoe racing to show how grateful we were for all their kindness. We suggested a model of East Anglian and Valiant to be given for a nine mile race on the triangle.

Two days later four cups left America in the Olympic with Roger. These cups had never before, in their 48 years' history, been won from America. The International Trophy, the National Sailiug Championship, the National Paddling and Sailing Combined Championship, and the Paul Butler Trophy were to sojourn in England for a year.

Roger and I had enjoyed our visit, for we had met in America canoe sailors who had fllled us with

"The stern joy which warriors feel

In Foemen worthy of their

steel"

.jpg)

Ulrike_veerkamp.jpg)

Ulrike_veerkamp.jpg)

Ulrike_veerkamp.jpg)